The Viral Fruit Cup Post

From Fruit Cups to Food System Change: Why a “Burn the Farm” Post Went Viral

This weekend, I sparked a lively debate on LinkedIn with a simple, provocative observation in the post below. A photo of a plastic fruit cup labeled “Pears grown in Argentina, packed in Thailand” is a globe-trotting journey for a few ounces of fruit. To add a taunt ripe for social media, I added:

If American farmers can’t improve food quality and beat this supply chain, they might as well burn the farm.

The post struck a nerve. Within 24 hours or so, it garnered over 54,000 impressions, with ~193 likes and 105 comments from farmers, entrepreneurs, and food experts sharing their thoughts.

Can U.S. farmers compete in a system where fruit travels 20,000+ km to be sold cheaply? (Link)

Why Foods with Irrational Supply Chains Persist

A look around the grocery store or supply chain news reveals many foods with seemingly irrational origins and journeys:

Fish with frequent-flyer miles: Wild Alaskan seafood is shipped to China for cheap filleting and packaging. Then, it is shipped back to the U.S., ending up labeled as “Product of China” despite being caught in America.

Chickens and seafood outsourcing: Poultry raised in the U.S. is shipped to Thailand or China to be processed and canned, then returned for sale.

Peruvian peppers via France: Canned peppers and artichokes from Peru are packaged in France and distributed globally.

Why do such bizarre supply chains persist? Economics. Global companies optimize every step for cost, even if that means a pear or a fish travels tens of thousands of miles. It can be dramatically cheaper to employ packing-plant workers in Asia or South America than in the U.S. or Europe. As one economics professor put it,

Since the globalization process began, [transnational companies] minimize costs by taking each part of the production process to the country where it is cheaper.

In Argentina, farmland and fruit might be cheap; in Thailand, packing factories and wages are cheap. By splitting tasks across countries, a company ends up with a lower total cost per cup of fruit.

Shipping cost is often minimal. Global freight routes have a massive scale and imbalances that make moving goods long distances very affordable. Ships that deliver Asian goods to South America or Africa often sail back half-empty, so they’ll carry goods ultra-cheap on the return trip rather than go empty. As a result, transporting pears from Argentina to Thailand and then to the U.S. might add only a few cents per cup. Sometimes, sending a container ship halfway around the world is less expensive than trucking the same goods within the United States. In our pear example, an asian packer probably had excess product and found a bargain buyer in the U.S., making the odd journey worthwhile.

Regulatory and market structures encourage these dynamics. Countries often impose tariffs on certain processed goods but not on raw produce, or vice versa, nudging companies to take specific steps abroad to dodge duties. Multinational food firms are adept at arbitraging every advantage: cheap land in one country, cheap labor in another, favorable trade terms elsewhere. Each business in the chain does what it does best or at the lowest cost.

Farmers, Foodies, and VCs Weigh In

My post sparked a significant amount of debate. Read them online and weigh in, please (link). Here are some highlights:

Eliot Frick (brand strategist): Eliot urged everyone to zoom out. “This is Burnham’s managerialism. Focusing on the absurdity of the supply chain is missing the forest for the trees.” In other words, Eliot suggested the fruit cup fiasco is a symptom of a deeper systemic problem, a managerial bureaucracy that optimizes for the wrong things. Blaming the pear’s journey alone might be missing the point. Frick hinted that entrenched corporate and governmental management, what James Burnham described as the “managerial revolution”, keeps the system stuck on autopilot, churning out cheap calories at scale while losing sight of nutrition or common sense. Elliot’s critique: Don’t just gawk at the silly supply chain; ask why the system encourages it.

Linn Steward (dietitian & blogger): Linn zeroed in on the cost vs. quality dilemma. She lamented that competing on price is a losing game for American farmers. “It’s probably time to burn the farm if we’re competing on cost,” she wrote, noting that U.S. chicken and seafood already get shipped to Asia for cheap processing. For fruit, she said, it’s a “mixed bag” – if Americans started judging fruit on quality and taste, the higher price [of local product] is justified. But I don’t hold out hope for that happening soon.” Linn’s perspective is a bit pessimistic: consumers could choose to pay more for a juicy, tree-ripened pear grown domestically, but most won’t. As long as we all buy on price, she implies, the lowest-cost (and often lower-quality) supply chain wins.

Jordan Pratt (agtech strategist): Jordan, an ag innovator, pushed back on the idea that American farmers are simply underperforming. The problem, he argued, is structural. “The problem with the production model in the US is not quality,” he wrote. “The US allows imports of crops from production models abroad that have labor at multiples below [our] cost… plus processors, CPG companies, and retailers soaking up profits. It is a misnomer to imply American farmers, in the current setting, have the ability to dictate prices or supply-chain metrics.” In short, don’t blame the farmers – they’re essentially price-takers in a global system. U.S. growers can produce high-quality food, but they’re undermined by cheap overseas labor and by powerful middlemen (big food processors and retail chains) that squeeze farmers’ margins. Pratt’s take highlights how farmers lack power.

Michael Mealling (venture investor): Michael, a tech VC with an eye on space and disruptive tech, echoed the need for outside-the-box solutions. He and others in the thread argued that tweaking the existing system isn’t enough; we need innovative disruption. As another commentator, Peter Cranstone, put it: “Looks like you need market innovation NOT technical innovation.” The issue isn’t that we lack the technology to can pears more efficiently; it’s that we lack new business models to get nutritious food from farm to consumer in a sensible way. Mealling’s perspective as an entrepreneur is that the food industry’s bureaucratic inertia, from government regulations to big agribusiness practices, won’t change on its own. It will take startups, new supply chain models, and bold ventures to break the status quo. In other words, expect meaningful change to come from innovators and outsiders, not the incumbent system that created the problem. Time for System C?

Other voices – consumer and systemic angles: Teresa Kelly, a local foods advocate, confessed, “I still cannot wrap my head around how this makes financial sense. And local food is such a hard hill to climb logistically.” Even those who want local, shorter supply chains find them painfully difficult to implement in practice, due to distribution challenges and a lack of scale. Others pointed out that consumers themselves share responsibility. We often choose the 4-pack of fruit cups for $2.50 without considering the broader impact. One person noted that we shouldn’t badmouth the American food system too loudly, as doing so can trigger defensive outrage from those invested in it.

The debate itself, with over 100 comments from across the food and tech spectrum, is a sign that people are no longer content to shrug and say, “That’s just how it is.” There is a growing consensus that something in the system is broken, even if opinions differ on how to fix it. A sign of opportunity?

Is a Fruit Cup “Real Food”

While the label on the fruit cup proudly listed its global journey, what about the ingredients and nutrition? The cup contained diced pears, packed in syrupy liquid. It looked like B-grade pears in fructose water. Dr. Robert Lustig might even call this “poison.” Single-serve fruit cups are basically fruit soaked in sugary syrup, a far cry from the whole fruit nutrition we’d hope for. Who thinks this is really what consumers want?

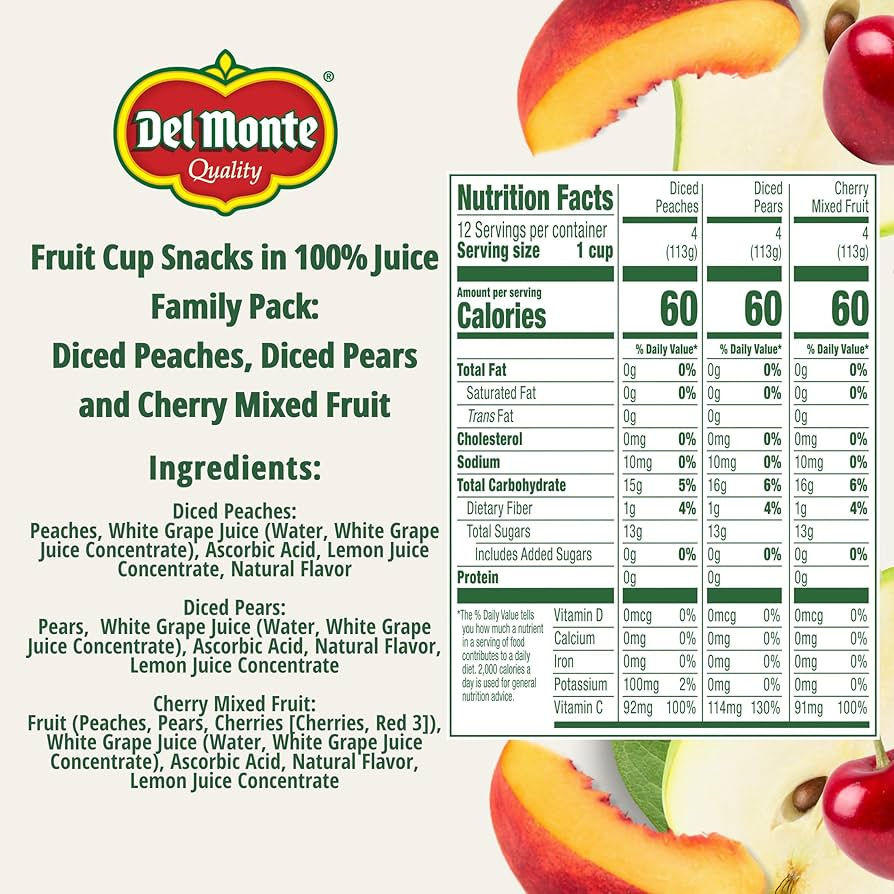

If you check the nutrition label of, say, a Del Monte or Dole fruit cup, a 4-ounce serving contains approximately 60 calories, with around 13 grams of sugar. One popular brand’s diced pears list “pears, white grape juice (from concentrate), ascorbic acid (to protect color)” as ingredients. They market it as “100% juice” packed, which sounds healthy, but nutritionally, it delivers a lot of free sugar (i.e. fructose) that's absorbed in the stomach to assault the liver. The fiber content is modest, 1 gram of fiber, versus ~4–5 grams in a fresh pear, because the fruit is peeled and cut, and some fiber is lost in processing. These cups often contain added vitamin C (ascorbic acid) as a preservative, which at least provides a vitamin boost. But beyond that, you’re getting a small serving of fruit that’s been cooked, sweetened, and sealed in plastic. A recipe to accelerate diabetes.

These fruit cups do start as real pears, but by the time they reach your spoon, they’re closer to a processed snack. They are convenient and do offer some vitamins and hydration, but they also introduce extra sugars and come in a single-use plastic tub. As a commentator noted…

U.S. has a wonderful pear crop, and a fresh pear has so much more nutritional value than ultra-processed pears in sugary syrup. Why are we importing lower-quality processed fruit when fresh, nutrient-dense fruit grows in our own orchards?

The answer, of course, is shelf life and price: that plastic cup can sit on a shelf for months and sells for cheap, whereas fresh pears are seasonal and perishable. From a nutritional standpoint, there’s no contest, real fresh fruit wins easily. The fruit cup’s label might boast “rich in Vitamin C” or “no high fructose corn syrup”, just fruit fructose…, but it’s certainly not the kind of “real food” that health experts extol.

Using Every Pear But At What Cost to Health?

One argument in favor of products like these fruit cups is that they help maximize crop yield and reduce waste. Not every pear is pretty enough to sell fresh at the grocery store. By processing surplus or “B-grade” produce, the smaller, blemished, or oddly shaped fruits, into cups, purees, or canned goods, producers ensure those fruits aren’t simply thrown out. In that sense, these global supply chains can be seen as extracting maximum value from every harvest. Nothing goes to waste. The pears in this case are likely from Argentina’s abundant Río Negro Valley, where they grow more than they can sell fresh. Instead of rotting, those pears took a trip to become a convenient snack for someone thousands of miles away. Economically, it’s a win-win: farmers get paid for fruit they might not otherwise sell, and consumers get a cheap product.

The public health trade-off is problematic. In the U.S. and many countries, diet-related illnesses like obesity and type 2 diabetes are driven in part by overconsumption of added sugars and ultra-processed snacks. A fruit cup might seem innocuous, but a steady diet of such “semi-real” foods can crowd out truly nutritious options.

To put it in perspective, America spends an estimated $1.9 trillion each year on healthcare costs due to poor nutrition. Yes, our little fruit cups utilize crops efficiently and provide a few vitamins, but they also deliver empty calories that, at scale, contribute to our chronic disease crisis. One LinkedIn commenter bluntly stated that we’d be better off not processing the pears at all, just eat them fresh, because the nutritional difference is so great.

Shipping fruit across oceans or keeping it shelf-stable often requires chemical help. Those Argentine pears were likely heated and sealed to sterilize them, and may contain acidity regulators or preservatives to maintain their texture and color. While the fruit cup label may not list many additives, the broader category of processed foods often contains sodium, preservatives such as sulfites, or artificial flavorings. The more we modify food to survive long-distance transport, the more we rely on substances that may harm our health in the long run.

These highly processed food products represent a trade-off between efficiency and wellness. They squeeze more economic value from each farm’s output (See Burnham). Every pear finds a consumer. But they also deliver poor nutrition. The public health community increasingly points out that cheap, long-lasting calories, such as processed snacks and sweetened drinks, are penny-wise and pound-foolish: we save money at checkout, but pay for it later via doctor’s bills.

One could argue that having fruit cups is better than having no fruit at all, especially in food deserts or off-seasons. Canned or cupped fruits can be part of a healthy diet if choices are limited. However, the ultimate goal should be to provide consumers with real, fresh, or minimally processed fruits and vegetables as much as possible.

Why Don’t Consumers Count Health in the Price Tag?

All this raises a pivotal question: If fresh, local, high-quality food is nutritionally so much better, why do consumers still opt for the cheap fruit cup? Why is price or convenience consistently winning out over health in purchasing decisions?

Several factors are at play:

The health costs are hidden: When you buy a $0.75 fruit cup or a $1 fast food burger, you’re not paying for the long-term health impact. If that snack contributes to obesity or diabetes down the road, the eventual medical bills are paid years later, often by insurers or society as a whole. There is a disconnect between the price at the register and the actual cost of the food. The U.S. spends roughly $1.9T on the healthcare costs of poor nutrition but only $1.7T on food each year. For every dollar we save on cheap food, we may be spending another dollar (or more) on healthcare. But consumers don’t see that linkage. It feels like someone else’s problem.

Marketing and availability favor the bad stuff: annually, the whole food industry (vegetables, fruit, dairy, meat) spends about $400M in marketing. CPGs spend nearly $14.5B marketing processed food. Consumers are bombarded with messages promoting convenience, taste, and low cost (often for processed foods), and they rarely encounter messaging about consuming more produce. Supermarkets likewise give prime shelf space to packaged goods with long shelf lives.

Convenience and habit: Consumers buy fruit cups not because they’ve done a nutrition cost-benefit analysis, but because it’s easy. The cups are pre-cut, portion-controlled, and don’t spoil quickly, making them ideal for throwing into a lunchbox with no prep. For a busy parent packing a kid’s lunch or a worker grabbing a snack, that convenience is worth more than the abstract notion of “this has 5 more grams of sugar than it should.” Habits and time constraints often trump nutritional ideals. If we’ve grown up thinking fruit cups or juice boxes are a normal part of a lunch, we won’t necessarily think twice about it.

Lack of clear information: A fruit cup sounds healthy. It’s fruit, after all, not a cookie. Packages boast “No High-Fructose Corn Syrup!” or “100% Vitamin C!” which can create a false sense of security. The subtle differences between whole fruit, fruit in 100% juice, and fruit in syrup aren’t apparent to consumers. Without clear labeling on added sugars or processing levels, people might not realize the health trade-off. This is where better labeling could make a difference. If the fruit cup had a big red label saying “+7g added sugar” or if products carried a score indicating how processed they are, a shopper might pause and opt for the fresh fruit instead.

So, how do we encourage shoppers to consider health when making their purchasing decisions? Education and transparency are key. Public health campaigns raise awareness, explaining that “cheap food isn’t really cheap when you consider medical bills”. Improved food labeling could nudge behavior. Some countries use “traffic light” labels on the front of packages to plainly mark high sugar, salt, or fat content. Imagine a fruit cup with a big orange light for sugar, versus a bag of fresh apple slices with a green light. That simple visual could sway someone to choose the apple.

Another idea is emphasizing nutrient density per dollar. If consumers saw a comparison that $1 of apples gives far more fiber and vitamins than $1 of canned pears, they might reconsider value. Currently, we compare foods by price per ounce or calories per dollar. But calories are not the nutrient we lack; if anything, we’re eating too many. It’s things like vitamins, minerals, protein, and fiber that we should maximize for the best value per dollar.

We can’t ignore access and preparation skills. Telling people to eat fresh pears instead of fruit cups won’t work if fresh pears aren’t sold in their neighborhood, or if they don’t know how to judge ripeness, or if they fear the fruit will spoil and waste their money. Community efforts, such as farmers’ markets, produce delivery services, and cooking classes, empower consumers to choose whole foods. If health is to become a factor in purchases, healthy choices must be accessible, attractive, and attainable.

Breaking the Cycle: Bureaucratic Inertia vs. Disruption

Why do we have a system that allows such absurd logistics to prevail? The commenters, especially Eliot Frick, alluded to the concept of bureaucratic inertia. Government agencies, big food corporations, and global trade frameworks are moving along their established tracks without reconsidering their fundamental goals. This is reminiscent of what Eliot called “Burnham’s managerialism”. In political theory, James Burnham argued that a class of managers and bureaucrats came to dominate decision-making, often prioritizing the perpetuation of their systems over innovative or radical change.

In the context of food, bureaucratic managerialism might manifest as follows: Governments set regulations that emphasize food safety, quantity, and affordability. However, they often measure success in terms of tons of output and calorie supply, rather than in nutritional outcomes. Large food companies, run by professional managers answering to shareholders, focus on quarterly profits and market share. To them, a supply chain that shaves 5 cents off each unit cost, packing pears in Thailand, is a win. There is no KPI that directly penalizes them for contributing to diabetes in 20 years or for hollowing out rural farm economies. Everyone in the system is managing their piece: logistics managers optimize distribution, procurement managers source the cheapest ingredients globally, and marketing managers advertise whatever sells. And the band played on……

One indicator of this system’s dysfunction is the aging of the farming population. As a commenter pointed out, the “average age of farmers in most ‘developed’ countries is hovering around 60 years old”, and there’s a dearth of young people willing to step into what looks like a financially hopeless career. That’s a huge red flag. It suggests that the current system, subsidized, industrialized, consolidated, and globalized, is failing to inspire or sustain the next generation of food producers. It’s effectively eating its seed corn, so to speak. Why would a bright young entrepreneur become a farmer today, when they see that even the best fruit can be undercut by cheaper imports and that farmers are often at the mercy of giant buyers and paperwork-heavy programs? “They don’t get the ‘creative’ part, just the ‘destruction,’” as that commenter wryly noted. This refers to “creative destruction,” the idea that industries must evolve or die – but in farming, it feels like mostly destruction (farm bankruptcies, rural decline) without much creativity or renewal.

So, how do we inject innovation and agility into such a system? This is where the concept of disruption comes in. The same force that’s upended industries from taxis (Uber) to banking (FinTech) to space travel (SpaceX). Eliot Frick’s critique implies that internal reform is unlikely; bureaucracies rarely reinvent themselves willingly. Instead, change often comes from visionary outsiders or maverick insiders who do something radically different. System C?

We can already see early signs of disruption in food systems: regenerative agriculture movements, direct-to-consumer farm boxes, alternative protein startups, and precision fermentation companies, to name a few. These innovators often face resistance, whether from regulatory hurdles or incumbent competitors, but they demonstrate what is possible. As Peter Cranstone said, market innovation is needed more than technical innovation. We possess the technical expertise to produce and distribute high-quality food; what we need are innovative business models and policy frameworks that prioritize nutrition and sustainability over volume and price.

One example is the push to measure food not just by safety/compliance but by nutrient density. Imagine if corn or peaches were graded and priced not only by bushels or cosmetic appearance, but by how much nutrition they deliver (vitamins, antioxidants, etc.). That could shift the focus from yield at all costs to quality of yield. Currently, a bureaucrat in the USDA or FDA is primarily concerned that a fruit cup meets labeling requirements and is free from pathogens, rather than whether it’s advancing public health. Changing those institutional priorities is hard, but not impossible, especially as the healthcare costs become unsustainable. While reform sounds advisable, the reality is that it will take entrepreneurial pressure, new companies making more money and improving, to compel the big players and regulators to follow suit.

In systemic terms, we’re talking about overcoming what is essentially a trillion-dollar momentum. The global food industry has been engineered over decades to produce ever cheaper calories, with lots of unintended consequences. There is a lot of institutional knowledge and infrastructure that keeps it that way. However, history shows that when a system is ripe for change, innovators can break through. Think of how Tesla ignored the entrenched logic of auto manufacturing (dealership networks, gasoline engines, etc.) and turned the car industry on its head by prioritizing technology and sustainability. Or how small organic and local farms, once dismissed as impractical, have grown into a force that even Walmart and Amazon have to reckon with as they stock organic lines and offer local produce delivery.

Eliot Frick’s point about not missing the forest for the trees is crucial. The pear cup is a tree. A stupid plastic cup of fruit. The forest is the web of policies, corporate incentives, and consumer habits that allowed that product to exist and be profitable. Tackling only the product, by shaming one company into sourcing domestically or a group of companies into stopping the use of artificial colors, will not solve the underlying drivers.

We need to overhaul how we define success in the food system. If the current bureaucracy is satisfied so long as there are ample cheap calories and all the checkboxes of safety are ticked, we’ll continue to see “pears packed in Thailand” situations. If, instead, the system’s goal were to maximize public health and minimize environmental impact, and we measured progress on those fronts, then we’d quickly find that shipping fruit around the globe in search of cheap labor is a failing proposition.

Innovative disruption is the mechanism by which we can jolt it onto a new path, optimizing for nutrition, sustainability, and community benefit. In part, creating a new bureaucracy, but in the process, changing our focus to the value of nutrient density rather than the value of cheap calories. Driving affordability by reducing the cost of healthcare.

Reframing Supply Chains: From Cheap Calories to Nutrient Density

If we accept that “food is health,” then our entire approach to food supply chains needs to be reframed around nutrition and wellness. For decades, the mantra driving supply chains was about producing more for less: more yield, more shelf-stable products, and more calories, all at a lower nominal cost. Governments prioritized food security in terms of preventing famine and maintaining low food prices. Businesses cared about efficiency and profit. Calories and compliance became the metrics of success: Is there enough food, and is it safe and cheap? By those metrics, a fruit cup that can sit for a year and costs under a dollar is a triumph. However, we now face new challenges: the prevalence of diet-related diseases, environmental strain, and consumers seeking genuine, healthy food.

What would it mean to design supply chains for nutrition and health first? It could involve several shifts:

Prioritizing nutrient density: Supply chains could be rewarded or optimized for delivering foods that have high nutritional value per unit. For example, shorter supply chains from farm to table preserve more nutrients. A carrot pulled from the ground and eaten within 3 days has more nutrients than one that has sat in storage for 3 months and then been canned. If we care about nutrition, we would invest in regional distribution hubs, cold chains, and quick transport for produce, rather than in processing plants that turn produce into less nutritious forms. This might mean a reversal of some centralization – e.g., having more localized packing facilities for fresh produce rather than one giant plant overseas.

Minimizing added sugar and additives: If health is the goal, supply chain practices that require lots of sugar, salt, or preservatives to make food last or taste “good” after traveling should be seen as inefficiencies or last resorts. Instead, the supply chain would aim to get foods to consumers in a state where they don’t need all that doctoring. Rather than converting a bumper pear crop into sugary cups, maybe excess pears could be quickly turned into unsweetened refrigerated puree, or dried into no-sugar-added snacks, or used in healthy school meal programs. Those might require more thoughtful logistics, such as refrigeration and quicker turnaround, but these are logistics that promote health.

Transparency and true-cost accounting: A health-first supply chain would likely include labeling or tracking of nutritional value along the way. Imagine if every product had to carry not just a nutrition facts label for the end consumer, but also a “nutrition preserved” score from farm to shelf. This could incentivize companies to avoid practices that degrade nutrition, like overly long storage or high-heat processing.

Regulatory shifts: If regulators reframed their mission as ensuring a healthy food supply, policies might change dramatically. For example, subsidies might tilt away from commodity corn and toward broccoli or pears. Food import/export rules might be revisited. Do we really need to import pears when domestic fruit is rotting, and could there be incentives to use local produce first? Perhaps there could even be taxes or tariffs that account for the health externalities, such as an import tax on foods with high levels of added sugars or ultra-processing, which would indirectly favor simpler, more whole foods in trade.

Stakeholders across the board, from farmers and entrepreneurs to policymakers and consumers, need to start valuing nutrition and health outcomes as much as, or more than, cost and convenience. This means building new metrics and narratives. For instance, rather than boasting “we deliver 100 million servings a year at 50 cents each,” a reoriented food company might boast “we improved the average nutrient intake of our consumers and reduced healthcare claims in our pilot region by 20%.” It sounds far-fetched now, but companies are moving in that direction. Some meal kit and food-as-medicine startups, for example, track health improvements in their customers.

Eliot Frick’s notion of missing the forest for the trees is apt. We must ensure that the new forest we grow is one where the trees are measured in terms of their impact on human health. It’s not enough to tweak one supply chain; the whole system’s incentives need realignment. Think of it like redefining success in transportation: for decades, cities prized moving the most cars as fast as possible, leading to highways, sprawl, and pollution. Now, many cities are redefining success as efficiently and safely moving the most people, leading to the development of bike lanes, public transit, and cleaner air. Food will undergo a similar shift: from maximizing cheap calories to maximizing healthy nourishment.

We are essentially rewriting the purpose of a massive global system. However, conversations like the one sparked by a humble fruit cup suggest that public sentiment may be ready. People are openly questioning why efficiency is defined so narrowly and whether compliance with outdated norms is enough. As one person in the thread said,

We’ve created a failing system for independent farmers, from government all the way down to consumers… If anything is in need of innovation, it’s our food system.

Reframing the system around nutrition and health would be exactly such an innovation – arguably the biggest since the Green Revolution. It means farmers wouldn’t just be volume suppliers, but stewards of public health. Entrepreneurs wouldn’t just chase margins; they would create value by improving lives. Consumers wouldn’t be passive price-seekers, but active participants in a food-health ecosystem. Capitalism would still thrive. Productivity would improve. Economies would grow.

It’s a big vision, but big visions are what drive big changes.

Farmers and Entrepreneurs as Food System Heroes

The system is absurd in many ways, but no, we don’t have to accept it as our fate. In fact, those on the front lines of food, including farmers, startup founders, scientists, and local food organizers, have a unique opportunity to rewrite the narrative.

History gives us examples of individuals and small teams overturning industry conventions. Elon Musk entered the automotive industry, which hadn’t fundamentally changed its supply chain or power source in decades, and in about 15 years, forced the entire global auto sector to start shifting to electric vehicles, largely by showing it could be done better. How? Partly by vertical integration and systems thinking. Musk’s companies famously avoid the complacent supplier networks and incremental mindset of incumbents. Tesla built a gigafactory, insourced many components, and tightly controlled quality and innovation. Controlling ~80% of its supply chain in-house. SpaceX likewise did things in-house that aerospace giants used to outsource. This vertical integration, essentially taking charge of your supply chain destiny, is precisely what some visionaries in food are now pursuing.

Take Fairlife, the dairy company often cited as a case study. Fairlife was started by a group of forward-thinking dairy farmers in partnership with Coca-Cola. They didn’t want to be just raw milk suppliers at the mercy of volatile prices; they wanted to create a value-added product and control its quality from end to end. Through ultra-filtration technology, they produced a novel high-protein, low-sugar milk and built a brand around it. The result? Fairlife has become one of the fastest-growing milk brands in the country, commanding premium prices and demonstrating that consumers are willing to pay more for superior nutrition and taste. Importantly, Fairlife operates with a vertically integrated model – they source from select farms (or farmer-owned cooperatives) and process the milk themselves, transforming it into value-added ultrafiltered products. By owning more of the chain, they ensured that the end product aligned with the health and quality promises, and they retained more profit with the producers rather than with middlemen. It’s a blueprint for how farmers can escape the low-cost trap: differentiate the product, control the supply chain, and sell on quality rather than quantity.

We see similar threads with other brands: e.g., Fair Oaks Farms (run by some of the same folks behind Fairlife) created a vertically integrated dairy/agritourism operation; Regenerative agriculture startups are connecting soil-health-focused farms directly to consumers who pay a premium for nutrient-rich, environmentally friendly produce; some grain farmers are banding together to mill their own flour and market artisan breads, rather than selling wheat at commodity prices. These are all entrepreneurial approaches to break free of the commodity treadmill.

Farmers can be more than producers; they can be inventors, brand builders, and leaders in their communities. Entrepreneurs, whether from tech or food backgrounds, can bring fresh eyes to problems like distribution and transparency. If a pear grown in Washington state is competing against a pear from Patagonia that’s packed in Bangkok, perhaps the solution is not for the Washington farmer to give up, but to team up with some innovators and find a way to get that pear to consumers in a form that highlights its superior freshness and flavor: a flash-frozen smoothie pack, a direct farm-to-table delivery, or a partnership with local schools for fresh snacks. There’s room for so many ideas when you stop assuming the current supply chain is the only way.

If the next generation sees that farming can help address healthcare issues, combat climate change, and provide a good living by eliminating outdated middlemen, they might flock to the field. We might soon talk about rockstar farmpreneurs the way we talk about tech entrepreneurs.

The LinkedIn fruit cup post may have started as a jab at supply chain absurdity, but ultimately, it’s about forging a food system that keeps people healthy. Achieving that means we cannot be complacent. As consumers, we shouldn’t accept trade-offs that make our food slightly cheaper but our bodies and communities less healthy. As producers and entrepreneurs, we shouldn’t buy into the narrative that “this is just how it’s done.” Every industry can be disrupted and improved – food is no different.

The next time you see a label like “grown in X, packed in Y” and shake your head, remember: behind that label are choices that people made, and people can make different choices.

No, we don’t need to burn the farm. We need to rebuild the system so the farm, the farmer, and the consumer all thrive together.

Your section on "Is a fruit cup 'Real Food'" is not accurate in regards to the nutritional value of the Del Monte canned fruit. The nutrition facts panels that are pictured clearly state 0g of added sugar, which means the product has not been sweetened at all. And your statement about fructose assaulting the liver is an oversimplification and quite frankly just fear mongering.

If you want to demonize canned fruit, then at least show products that are packed in light syrup and have the nutrition facts to show. Canned fruit with 0g of added sugar has a lot of nutrition to offer.

Unfortunately we have “leaders” who cannot understand the financial dynamics of much of anything. Here in the Northwest we are short guest worker permitted labor (I’ll let you guess why), so the apple and cherry harvests will not be completed before the fruit is compromised … will likely end up as juice in fruit cups